A home health provider has helped a hospital reduce readmissions of highly at-risk patients by 60%, through a program that relies in large part on community health workers.

Like other hospitals around the country, University of Maryland St. Joseph Medical Center (UMSJMC) has been looking for ways to cut its readmission rate, given that payments are being tied to this metric. As part of that effort, the 232-bed nonprofit hospital just north of Baltimore has been seeking out new partners to help coordinate care across the continuum.

It found such a partner in Maxim Healthcare Services. Based in Columbia, Maryland, the company provides home health, medical staffing, and other services nationwide.

“I think our conversations with the hospital really focused on a different kind of approach,” Maxim’s Vice President of Government Affairs and Product Development Andrew Friedell told Home Health Care News. “One model was to bulk up your typical home care services and look to provide more [of them]. I think we really looked at it from the beginning that the traditional services weren’t working for this patient population, and so we needed to look at what really had to be addressed.”

The patient population in question was one at high risk of readmission based on four factors: psychological factors (anxiety/depression/personality disorders, etc.); social determinants (housing, lack of transportation, etc.); medical comorbidities (such as having hypertension and diabetes); and poor functional status (difficulty with activities of daily living). All the UMSJMC patients who faced risks in all these areas and were being discharged home were candidates to participate in the program that launched in February 2016.

That program involves a visit from a nurse practitioner while the patient still is in the hospital, to begin formulating a post-discharge plan of care. That plan is further refined by a registered nurse who visits the patient at home shortly after discharge. A community health worker (CHW) then gets involved to help with the execution of the plan, particularly with regard to overcoming barriers such as lack of transportation to follow-up physician appointments, Friedell explained.

While all the CHWs make sure there’s a primary care physician in place for the patient, and that the patient has a way to get to a follow-up appointment within the first 14 days at home, beyond that they are providing a variety of case-specific services. For instance, they might be enrolling a patient in an addiction counseling program, or meeting a patient at the supermarket to help shop for nutritious foods, or helping the patient get involved in Meals on Wheels or similar services, Friedell said.

Addressing the psychological factors and social determinants that often cause readmissions separates this program from others, Friedell believes. Others support the view. The strong relationship between these factors and health—both at an individual and population level—is a notion supported by theory as well as empirical evidence, says Steve Du Bois, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist and professor of psychology at Adler University in Chicago. Du Bois teaches the course Social Determinants of Mental Health.

“Programs that emphasize and address these systemic factors, such as continued access to health care, transportation, and health education, likely will facilitate not only acute recovery but also long-term health and well-being,” Du Bois tells Home Health Care News. “Psychology, public health, medicine, and more fields—we’re all understanding more deeply the impact of social determinants.”

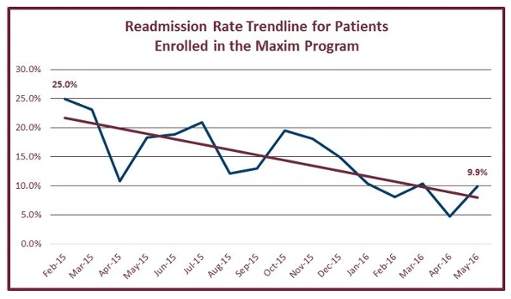

So far, it appears that the Maxim program is adding more evidence to support the importance of a multidimensional approach to risk identification and interventions. Maxim and UMSJMC have data through May 2016. In that period, the program involved about 1,800 patients overall. It has driven the readmission rate down for this patient group by more than 60%.

It’s difficult to attach a cost savings to that reduction, Friedell said, because there’s not a control group to compare against. The provider organizations are keeping track of readmission trends to measure success.

A workforce opportunity

While the program is saving money in the form of reduced readmissions, implementing it did come at a cost, including hiring community health workers. Startup costs were covered by the hospital, which viewed this program as an investment, Friedell said. Still, the nurse practitioners, RNs, and community health workers involved all are on Maxim’s payroll.

Home health providers that want to be attractive hospital partner may think about creating a CHW workforce of their own, even if they have to bear the costs themselves. In fact, there’s a tremendous opportunity to develop this workforce across the industry to help drive down costs while improving outcomes, and it’s an area that Maxim is focused on, Friedell said.

However, there are some impediments to developing a CHW workforce, which Maxim noted in a recent white paper prepared with Leavitt Partners.

“Despite CHWs’ increasing use and support, the workforce remains fractured, and there are still many challenges to overcome,” the white paper states. “Training is inconsistent, qualifications vary, and funding mechanisms are few.”

States are starting to address some of these barriers, such as through training/certification standards. But providers that are incorporating CHWs into their workforce may find few models to emulate, and will in effect be creating their own templates for what this role entails and who best fulfills the duties.

It may be possible to find current caregivers who are good candidates to become CHWs, but there are important distinctions between, say, a care aide and a CHW that agencies need to keep in mind, Friedell said.

One major distinguishing characteristic of a good CHW is that he or she is highly engaged in the community and has strong connections there. That not only means that the community health worker will be aware of different resources available in the area, but will have the credibility in the local area to be able to connect patients with the needed services. It also should help the CHW forge a strong bond with patients.

“Part of it is that they come from the communities they’re engaged with, so they’re embraced by and trusted by the patients,” said Friedell. “That’s the value they have, that they relate to the patients and develop a bond with them, while there [may be] barriers between patients and other caregivers.”

In addition to considering the CHW’s community relationships and patient interaction skills and duties, a provider bringing in these workers should consider the organizational structure needed, the white paper advises. This includes training, clinical oversight, team participation, and methods of evaluation.

Written by Tim Mullaney

Companies featured in this article:

Maxim Healthcare Services, University of Maryland St. Joseph Medical Center