Home care agencies throughout the United States often face difficulties in finding and keeping their caregivers, which are tasks sometimes made even more challenging by providers’ inability to offer competitive wages and steady hours. Honor, buoyed by scale and a technology platform, says it’s succeeding in cracking the retention code.

The San Francisco-based home care company, which currently operates across California, New Mexico and Texas, has the data to back that claim up as well, Austin Harkness, head of care at Honor, told Home Health Care News.

“There’s a lot of different ways that [turnover] is calculated, but, as we look at our retention of care professionals who come on our platform and serve our clients, we’re well below the industry’s average mark,” Harkness, who joined Honor about a year and a half ago, said, though he declined to share specific numbers.

The overall turnover rate for the home care workers is believed to be somewhere between 40% and 60%, previous industry research has found.

To help gauge its success in retaining those care professionals, or “care pros,” Honor conducts an internal quarterly survey evaluating job satisfaction. This quarter’s survey results were particularly encouraging.

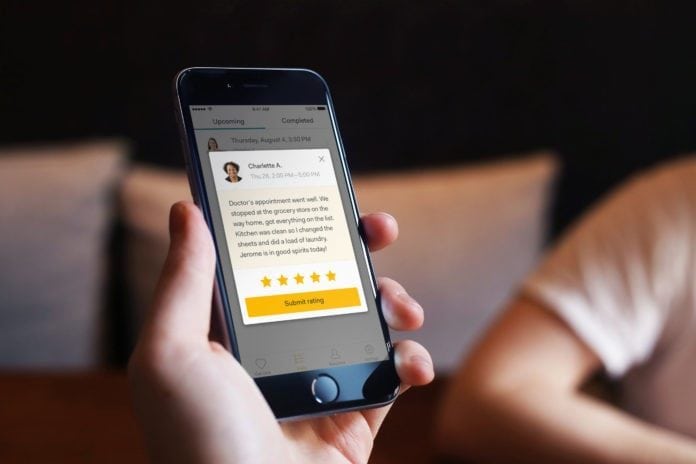

Nine out of 10 of Honor’s care pros surveyed either “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that they enjoyed using the Honor app in their work, for example. Similarly, roughly one-third of care pros reported that they would not change a single thing about working with Honor.

“If you think about what care pros really care about, it’s the same thing our clients care about, which is transparency and control,” Harkness said. “Our technology provides that transparency. We operate in an industry where a lot of caregivers go into a home to serve a client not always knowing what they’re walking into.”

Honor’s most recent survey also revealed that the company carries a care pro net promoter score (NPS) of 78%.

In general, an NPS is a management statistic that ranges from -100% to 100% measuring loyalty and satisfaction. A higher NPS is, of course, more desirable, Harkness said, adding that Honor’s is broadly in line with what innovative companies such as Google and Apple see.

“That’s hard to replicate,” he said. “We’re in pretty rarefied air in terms of workforce NPS level.”

Since launching in 2015, Honor has raised more than $115 million in venture capital funding, backed by Naspers Ventures, Andreessen Horowitz and Thrive Capital. As part of its business plan, Honor partners with local home care agencies to manage their scheduling, payroll and other back-office logistics, while also sharing from its large pool of care professionals.

Leveraging scale and tech

Focusing on caregiver satisfaction and retention levels is important for Honor, but also other agencies home care providers, especially as the industry grapples with a daunting caregiver shortage crisis.

Nearly 2.1 million home care workers currently support seniors and individuals with disabilities. That workforce has more than doubled in size over the the last decade and will need to continue growing, as the U.S. population of 65-and-older adults is projected to skyrocket from 47.8 million people to 88 million by 2050, according to New York-based research and consulting organization PHI.

“Throughout the country, agencies are reporting shortages and difficulty hiring [caregivers], which is not hard to understand given how difficult the work is and how low-paid it is,” Paul Osterman, a low-wage labor market expert and professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management, said. “And things are only going to get worse. We’re heading toward a perfect storm in terms of [labor] shortages.”

Besides retiring baby boomers, rising wages in the retail and fast food sectors will also contribute to the crisis, according to Osterman. Annual wages for U.S. home health and home care aides normally hover around $18,000 per year, he said.

“At the end of the day, the hourly wage is going to be critical in terms of getting people to work as home health aides instead of greeters at Walmart,” Osterman said. “If greeters can make $15 an hour working at Walmart, that’s stiff competition.”

Osterman recently highlighted the looming caregiver shortage crisis as part of a PBS NewsHour report.

While improving compensation for workers is a surefire way to strengthen recruitment and hiring, it’s not the only step agencies can take. A lot of workers leave the home care industry because of unstable hours and a lack of job support, according to Osterman.

“Many agencies could improve their scheduling routines so caregivers can get more stable hours or additional hours,” he said. “That would improve things somewhat, though you do see high-quality agencies making an effort to do this already.”

That’s been a major part of the retention success for Honor, which expects to see its top-line business triple this year.

Through its technology platform, Honor gives its care pros the power to choose when and where they work based on skill set, geography and availability. Honor’s tech also gives workers access to a 24/7 support team for fielding any concerns.

“Because we provide them with that level of control, that transparency and consistency in hours, that gives us a fundamental leg up in the industry in becoming an employer of choice,” Harkness said. “What I think really differentiates us in the marketplace — and what makes us a great place to work for a care professional — is our scale and technology.”

Scouting for talent

In addition to using its scale and tech, Honor has taken more simplistic measures for retaining and recognizing workers. That includes this past Mother’s and Father’s Day, when the company sent care packages to its care pros, each with sleep masks, slippers and other items.

Despite its success in retaining employees and keeping them happy, Honor understands there will eventually come a time where it has to look outside the traditional labor market for prospective care pros.

“With 10,000 Americans turning 65 every day — and that trend continuing over the next decade — we’re going to have a shortage,” Harkness said. “We spend a lot of our time getting better at identifying, assessing and training great care professionals with existing industry experience, but we know we’re going to have to ultimately start to dip into adjacent talent pools and develop those individuals.”

To find those workers, Honor has begun studying the intrinsic values that make a person a high-quality care professional, he said, such as a service-oriented temperament.

Honor has not yet had to reach out to individuals without relevant experience, according to Harkness.

Written by Robert Holly