Over the past several years, many states have strengthened their home- and community-based services (HCBS) programs by covering more services and increasing rates.

Now, over a dozen members of Congress are trying to give states additional funding to help expand those HCBS programs further.

“A vast majority of seniors and people with disabilities would prefer to receive care at home or in their communities,” U.S. Sen. Bob Casey (D-Penn.) said in a statement. “Unfortunately, because of our nation’s caregiving crisis, home and community-based care has become increasingly difficult to access. By stabilizing and investing in the caregiving workforce, we can better provide seniors and people with disabilities with a real and significant choice to receive care in the setting of their choosing.”

Casey, the chairman of the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, introduced the Home and Community-Based Services Relief Act this week with 17 of his colleagues. The legislation would provide dedicated Medicaid funds to states for two years in hopes of stabilizing their HCBS service delivery networks.

The legislation also aims to help states recruit and retain HCBS direct care workers.

Currently, all 50 states and Washington, D.C., provide HCBS to eligible adults 65 and older — and certain other populations — through a combination of state plan benefits and waivers. However, the specifics of those waivers and benefits — what those services are, who is eligible, how they are eligible, how many people are served, etc. — vary greatly from state to state.

What also varies by state is what specific HCBS services are covered under a state’s Medicaid waiver. Federal Medicaid statutes require states to cover institutional long-term services and supports (LTSS) and home health care, but the rest of HCBS are optional.

A vast majority of seniors on Medicaid want to receive LTSS in their home. Due to staffing shortages and a lack of funding, it’s becoming more difficult for HCBS providers to offer their services to more seniors.

If the new bill passes, states would receive a 10-point increase in the federal match (FMAP) for Medicaid for two fiscal years to bolster HCBS.

Those federal funds could be used to increase direct care worker pay, provide paid family or sick leave, and pay for transportation expenses for members receiving HCBS care.

Katie Smith Sloan, the president and CEO of LeadingAge, urged every lawmaker to sign the “important legislation.”

“Older adults and families are facing a crisis in access to care in HCBS and across aging services – a situation that, given our aging population, will only grow more dire if no action is taken,” Sloan said in a statement sent to Home Health Care News. “Home health providers are already forced to reject referrals due to workforce shortages, an extremely competitive labor market, financial pressures and drastic cuts to Medicare payment rates in 2023. The kind of support Sen. Casey’s bill offers for providers of home health and other services is massively needed to keep the country’s ability to support older adults intact.”

The current administration has been vocal about its support for HCBS.

When National Association for Home Care & Hospice (NAHC) President Bill Dombi left a home health care-focused hearing in D.C. earlier this month, he did so buoyed by that support.

“Candidate Biden on the campaign trail was really pushing for home care, and he’s mentioned home care in his two consecutive State of the Union addresses, the first time ever from a president to bring about home care,” Dombi told HHCN earlier this month. “That focus on home care was home- and community-based services, be it Medicaid or otherwise, and a focus also on the workforce. A focus on the direct care workers and their compensation levels and the waitlists for beneficiaries in Medicaid waiver programs for home care services.”

HCBS woes

The new legislation comes a day after the Kaiser Family Foundation released a comprehensive survey that showed all states are dealing with workforce shortages in HCBS, and 49 states are dealing with shortages in more than one area of the workforce.

According to the survey, all 50 states and D.C. reported shortages of HCBS workers. the majority of which were among direct support professionals, personal care attendants, nursing staff and home health aides.

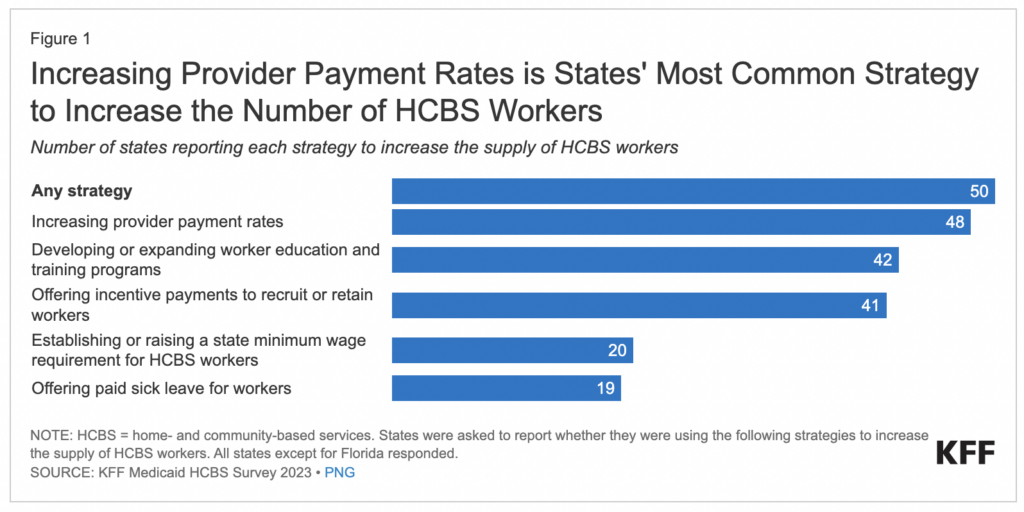

To combat those shortages, states have overwhelmingly increased provider payment rates while also developing or expanding worker education and training programs.

“Such shortages may reflect ongoing effects from the pandemic, but also low levels of compensation coupled with increasing requirements of providers,” KFF wrote in its survey summary. “In the summer of 2021, HCBS providers in focus groups reported that their jobs had high physical demands and mental demands that were often ‘overwhelming.’ The groups described their wages as low, particularly given the demands of their jobs; and how staffing shortages made their jobs harder because they may not know if they would be able to leave work at the end of their shift.”

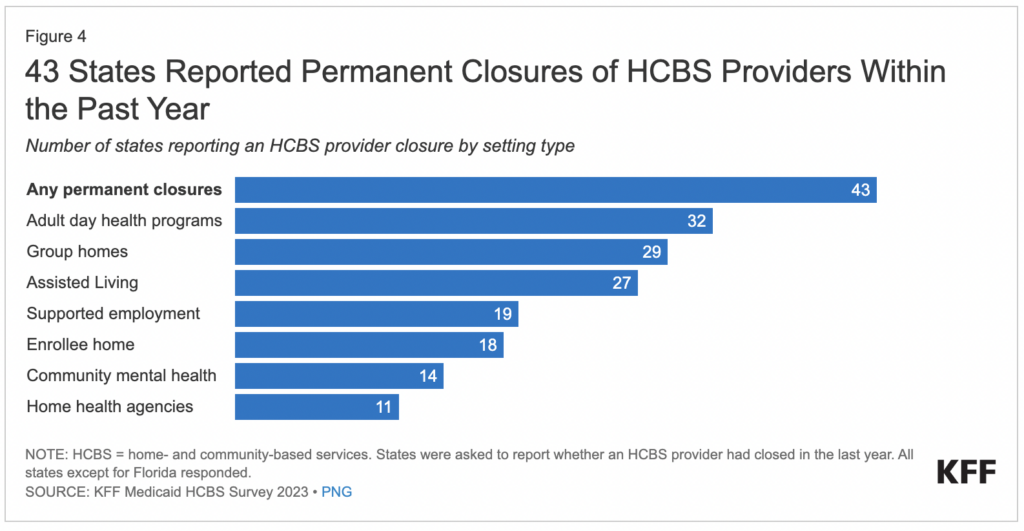

These shortages are now leading to crippling closures across the country.

Within the last year, 43 states experienced permanent closures of HCBS providers. Those closures were most common among adult day health programs (32 states), group homes (29 states) and assisted living facilities (27 states).

Between 10 and 20 states reported closures of supported employment providers (19 states), providers working in enrollees’ homes (18 states), community mental health providers (14 states) and home health agencies (11 states).

Possible solutions

A majority of the states (48) told KFF that they have increased payment rates for HCBS workers in order to address these woes.

However, state budgets are already tight to begin with. Expanding worker education and training programs, incentive payments for recruiting and offering paid sick leave for workers are some other options states have used to address these issues.

“States also reported several other types of initiatives to strengthen the workforce including creating platforms or support systems to connect job seekers with employers and positions, launching a social media campaign, and providing outreach to prospective employees,” KFF wrote.